The Trolley Problem: Human vs. Robot Edition

Morality, blame, and omission-comission bias

I was scrolling through some old newsletter pieces I wrote and came across a fun one on AI and the trolley problem. Given how much Chat-GPT3 has been in the news recently, I thought this would be a timely one to adapt and update.

The trolley problem is a famous thought experiment in human ethics first introduced by Phillippa Foot.

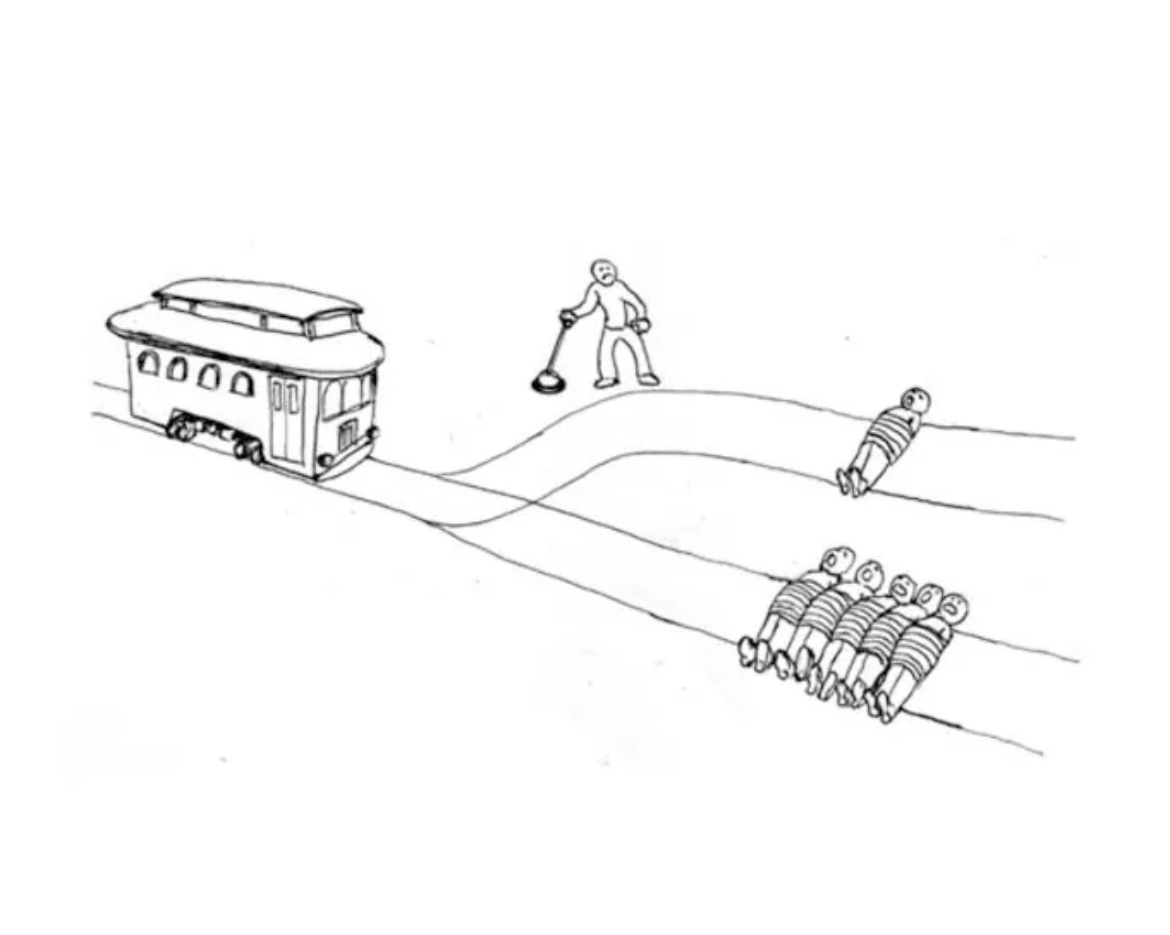

It goes like this: A trolley is barreling toward five people standing on a track. The only way to save them is to pull a lever, diverting the trolley to a side track where one person is standing. Pulling the lever will save the five people but kill the one person on the other track.

That’s you standing next to the lever. What do you do?

(Image from this article by Brian Feldman in New York Magazine)

A utilitarian would obviously pull the lever, sacrificing the one person to save five.

As you likely already know, not everyone is a utilitarian. In fact, a full 30% of people think it is not even permissible to pull the lever and about 50% of people think it would be morally wrong to do so.

That’s what humans think about other humans making the decision about diverting the trolley.

But what do humans think about robots who pull the lever? Do humans hold AI to the same ethical and moral standards as they do other humans?

That’s the question that Bertram Malle and colleagues asked in a study that looked at the differences in how we expect humans and robots to act when presented with the trolley problem.

What do people think is the moral choice for a robot?

Are robots expected to pull the lever?

Do we blame them for the deaths that result if they do pull the lever?

Do we blame them for the deaths that result if they don’t?

Malle found surprising differences in how we view permissibility, moral wrongness, and blame for humans versus robots in the trolley problem.

Humans blame humans significantly more for the outcome resulting from pulling the lever (one death) than for the outcome resulting from letting the trolley continue on its path (five deaths).

But they blame robots only very slightly more for pulling the lever. Damned if robot does, damned if robot doesn’t.

When it comes to moral judgment, there is an even bigger difference between the way we think about humans and robots.

When humans are making the decision, 49% of people think it is morally wrong for a human to pull the lever and divert the trolley (killing one person instead of five), while only 15% of people think that a human who lets the trolley stay on course (killing five people instead of one) is morally wrong.

People think it is a much greater moral wrong for a human to pull the lever than to let the trolley stay the course.

But when it is a robot pulling the lever, the pattern flips.

Only 13% of people think the decision to divert the trolley is morally wrong for the robot. But when a robot lets the trolley stay on course, 30% of people think it is morally wrong for the robot to fail to pull the lever.

So what’s the deal? Why do we want the robot to pull the lever but think it is morally wrong for a human to do so?

I good guess is that it has to do with omission-comission bias.

Omission-commission bias describes an asymmetry in how we process bad outcomes that result from an action vs. bad outcomes that result from inaction or a failure to act. We both regret bad outcomes more keenly that result from action than those that result from inaction and we blame others more for bad outcomes that result from committing an act rather than from omitting to act.

This is true even when the harm that results from the omission is greater than the harm that results from the commission, as Jon Baron’s foundational work in the 90’s on on vaccine hesitancy demonstrates (long before all the brouhaha about the Covid vaccine!).

Baron’s work shows that even when the probability of harm from getting a disease is far greater than the harm that might result from getting the vaccine, people will still be hesitant to vaccinate, focusing more (in terms of regret and blame) on the bad outcomes that might result vaccinating (sickness, injury, death) rather than the bad outcomes (sickness, injury, death) that might result from the failure to vaccinate.

What omission-commission bias tells us about humans and the trolley problem is this: People can anticipate that others will hold them to greater account for the one death that results from taking action and diverting the trolley vs. the five deaths that result from a failure to pull the lever, even though diverting the trolley results in less harm since fewer people will die.

We blame others and we know others will blame us, so we don’t pull levers when maybe we should.

It’s better to let the train go down the track it’s already on if we’re much more likely to be blamed for diverting the trolley than for doing nothing.

It’s better to stay in a job you are certain you hate for fear that you might hate the new job you take, even if the probably you hate the new job is much lower.

It’s better to not fire that employee who is a B-player for fear that the next person you hire might not work out.

The regret we feel when we get a bad outcome from switching is greater than the regret we feel from sticking with the status-quo. The blame we assign when someone gets a bad outcome from switching is greater than the blame we assign when sticking with the status-quo.

We prefer, proverbially, to let nature take its course. But that’s for humans.

When it comes to a robot, omission-commission bias no longer appears to apply in the same way or to the same degree.

Malle’s data bears this out: humans expect moral humans to choose inaction. But humans expect a moral robot to choose action and pull the lever. We blame humans who pull the lever and let those who do nothing off the hook. But robots get about the same amount of blame whether they pull the lever or not.

It doesn’t so much matter whether one person or five people die. Someone dies and the robot takes the heat either way.

This is more than just about robots and runaway trolleys. Malle’s work has implications for how we might accept bad outcomes for things like autonomous vehicles.

An autonomous car veers to save a pedestrian in a crosswalk but kills the passenger as a result? Blame the car.

Save the passenger but kill the pedestrian? Blame the car.

This is serious stuff as we think about not just the ethics of AI but also whether people will accept the consequences of these kinds of trade-offs.

I don’t think all technology/robots/algorithms are improvements over humans. Humans have some pretty big advantages of their own when it comes to decision-making and sense-making over an AI. I also have real doubts about what AI is going to mean for misinformation (for more on that, check out Gary Marcus’s excellent substack, The Road to AI We Can Trust).

That being said, if we want any benefits of technology potentially improving our decisions, we can’t discourage such technology by blaming it for outcomes for which a human would escape blame.

We're a remote company and most things happen async on slack. We've built some slackbots that nag people when certain things don't happen when they're expected to instead of various managers having to do the nagging. The employees seem to be much less "annoyed" by the bot doing the nagging than the manager doing the nagging. Feels similar, but can't quite put my finger on whether it's the same.